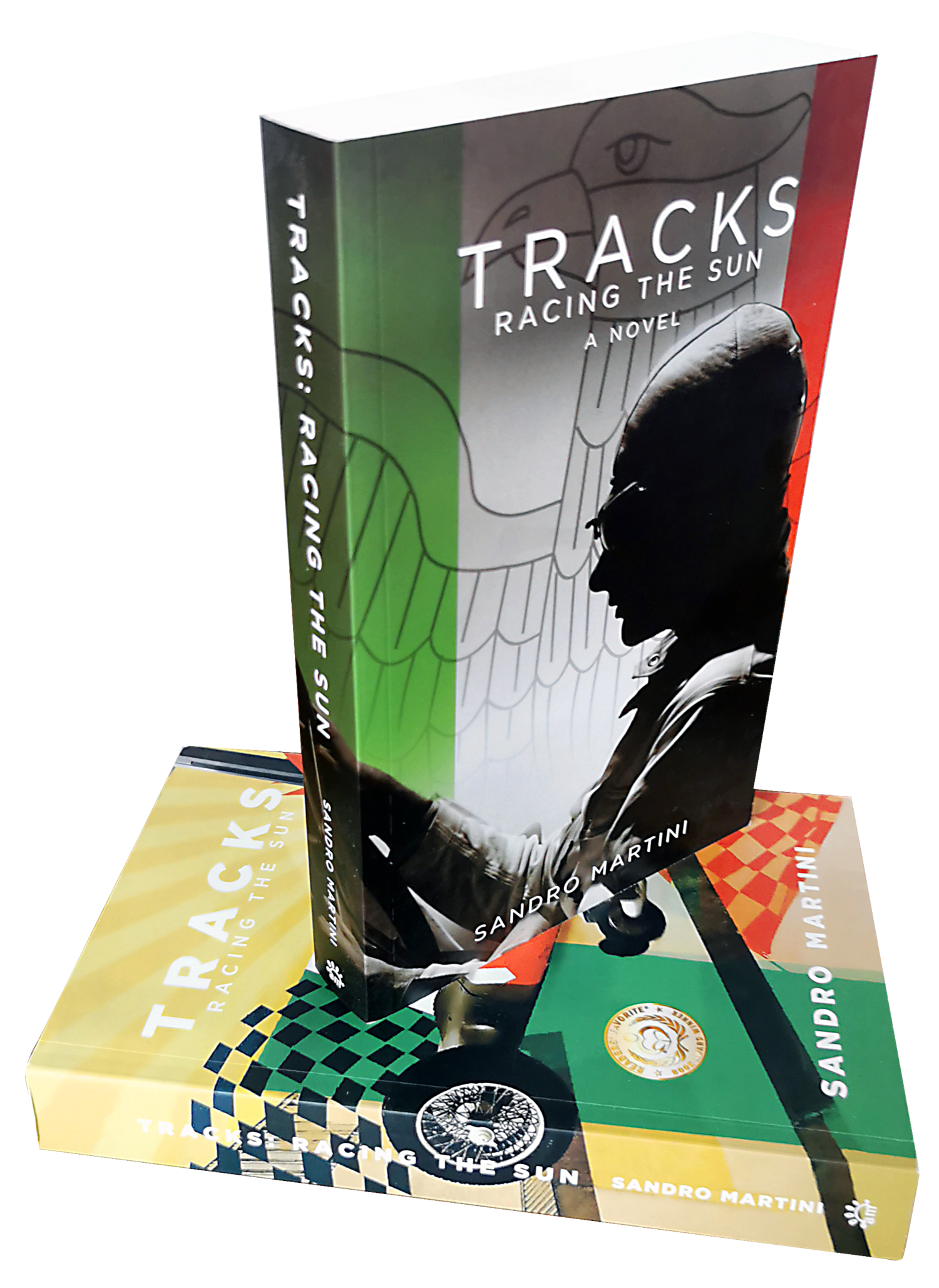

Tazio Nuvolari was an Italian Fascist hero who once admitted to never having experienced fear, and whose chosen destiny was to die on the tracks that he dominated in his Alfa Romeo. Life, though, would have a far more sinister hand to play: the man many regard as the greatest racing driver in history would live long enough to understand death: the death of friends and of fellow racers, but most of all, the death of those he loved the most.

Achille Varzi was the taciturn, inscrutable Italian who became the world’s highest paid sportsman when he joined the Nazi-funded Auto Union team in January 1936. Twelve months later, he had stolen another man’s wife, lost his reputation along with his career, and vanished into the shadows of an opiate addiction that would almost claim his life. Hated by the Fascists, scorned by his fellow drivers, he was a man who thrived on the animosity he nurtured.

Rudi Caracciola was the German ace known as the man without nerves, a man from nowhere who had escaped an act of brutal violence in his youth. His singular desire to be a race driver—allied with an indomitable spirit—saw him become one of the world’s top drivers by 1933. That was the year he put his Alfa into the wall at Monaco: By the time he left hospital seven months later, his nerves as shattered as his hip, he’d lost his career to younger men, and his wife to a skiing accident. Alone, constantly in pain, and with a limp from a leg that had almost been amputated, he set about re-building his life with an ice-cold determination. He remains the fastest man ever on a public road—a record that has not been bettered in 80 years.

Bernd Rosemeyer was the youngest of the four, a provincial boy brought into the Auto Union team as much for his looks as for his talent. Blonde blue-eyed Bernd was a Nazi wet-dream, a member of the SS, and the very definition of the promise of Hitler’s youthful Reich. He was the most successful propaganda tool Goebbels ever had, Bernd the poster-boy, used to inspire the children of the Reich to conquer or die—and for the Nazis, a dead Bernd was more valuable than a live one.

Ilse was Paul Pietsch’s wife when Varzi first saw her. It took only a few months before they began their affair. In less than a year, Varzi and Ilse had vanished from the grand prix scene. It would end when Mussolini would prevent Ilse from returning to Italy, and with Varzi in a rehab clinic. The last anyone ever saw of Ilse was in 1939, just before the war, when she tried to commit suicide. After 70 years, author Sandro Martini tracked her down for Track Racing the Sun.

Ilse and Varzi: a tragedy in 2 parts