A Missing Chapter From TRACKS - RACING THE SUN

The original novel was about double the size of the novel eventually published. A lot of scenes ended up on the cutting room floor, enough, I think, to probably create another novel featuring Caracciola and Bernd Rosemeyer. One of the scenes that was heavily edited was this one.

CUT SCENE FROM

TRACKS RACING THE SUN

SANDRO MARTINI

Caracciola and his first love, Charly, in the late 1920s: Charly died young in an avalanche while 'Caratch' was recovering from his life-threatening shunt at Monaco in 33, an accident that saw him lose three inches from one leg, and forced him to race in pain for the rest of his life. In the background is a slim Alfred Neubauer, a year or so since retiring as a top driver for Mercedes.

The Roxy Bar, Berlin, May 21, 1932

Berlin’s silence was both troubling and reassuring. The SS and the SA, some weeks earlier, had been banned from public displays of strength and humiliation which seemed to me to be about all the German soul required, and the streets had returned to the chilled indifference of my memory, silent of the half-million men whose songs had so intrigued at last year’s race. Blood must flow, they’d chanted, blood must flow! Blood must flow as cudgel thick as hail! Let’s smash it up, let’s smash it all up, this goddamned Jewish Republic. Back in Italy, the squadristi had been in a similarly nihilistic mood a decade earlier, an acrimony that’d ended with Mussolini’s triumphant March on Rome. Whether the ban on youth would avoid what seemed an inevitable showdown between those who’d failed post-War Germany (and cruising the windswept streets in my taxi, it was difficult not to empathize with the misery under which the residents of this city lived their pasty, savage lives) and those who saw in its dismantlement salvation, was a question that engorged the editorial columns of Berlin’s dailys. At the Roxy though, the Depression and the cold had as much chance of gaining entry into the opulence that lay beyond the sagacious brick walls of its façade as a local SA street tough. The club been made popular by Max Schmeling, the heavyweight boxer, and tonight, on the eve of the motor-race at the AVUS, the club, I knew, would be beaming enough jewels to end all of history’s depressions—economic and otherwise.

I’d barely handed my loden coat over to a half-naked coat-check girl when a grave arm embraced itself about my throat and a voice—smelling of cigars and cognac—whispered, ‘You are Johnny Finestrini, ja? The famous journalist?’ Bright, merry, queerly expectant eyes stared down at me. I glanced beyond them to the drawn, black velvet curtains that shielded the innards of the Roxy from the vestibule.

‘Have we met?’ I asked the tetragon, squashed face of this tall man who was, I gathered, either a exceptionally poor or brave ex-boxer.

‘By no means, no sir, by no means. My name is Ditgens—you can call me Heinz. This is my club.’

I looked down but no hand was being proffered. ‘How did you know who I was?’

‘Yes well,’ Ditgens’s eyes gelled solid, little marbles of color, ‘there’s the thing, yes sir, there’s the thing.’ His arm, tightened on my shoulder, gave him leverage as that broken face closed in tight to whisper, ‘Do you know a man named Hanussen?’

‘Doesn’t,’ I replied, hearing voices rise amidst applause from somewhere beyond the velvet curtains, ‘sound familiar.’

Ditgens’s face bowed; this the bad news he’d been expecting. His considerable jaw indicated the bat-wing-like curtains that he separated between his paws like a stripper with stage fright peering at a hateful audience. ‘Centre table,’ he said, tempting me closer. ‘Do you see it? There, by the pillar?’

My attention floated to the stage where three naked girls were in the process of slapping their pubic hair—and didn’t progress much further.

‘There,’ insisted Ditgens, one bit-to-the-quick finger aimed at a table floating like an island within a panacea of profound lushness. There was, I thought, a seductive aspect to such wanton, naked displays of wealth. The faces around the table were instantly recognizable to me. Prince Lobkowicz, the Bohemian royal from the House of Lobkowicz (one-time patrons of Beethoven) who’d bought his seat in the Bugatti team and, I suspected, at this table tonight, sat beside Louis Chiron and Achille Varzi, both in startlingly white smoking jackets. Opposite them, with the back of their heads to me, the unmistakable squareness of Rudi Caracciola and the blonde locks of his wife Charly sandwiched Baby Hoffman. At either end of the table there were the two German aces, Hans Stuck, and the Prussian nobleman Manfred von Brauchitsch whose family, if you read the gossip pages, had invented the German army, and whose uncle Walther had been appointed to the General Staff during the War. Manfred was, I’d been told by the journalist Paul Levant, the next Otto Merz, and it was the possibility of an interview with him that had enticed me to the Roxy that night. Von Brauchitsch’s destiny, Levant had told me—to follow in the bootsteps of generations of Teutonic warriors—had been curtailed by the War and the arrival of the peacenik Weimer Republic. Generations of aggression in a time of peace had seen young Manfred reject cadet school for years of hard-living that’d ended one night in the fall of ’28 with him and his motor-bike wrapped about a pole in downtown Berlin. He’d been then sent to convalesce in the baronial splendor of a castle in Brühlschen, and it was there that he’d first tasted the thrill of racing, in a sleek Mercedes SSK belonging to his cousin and with which he’d won his first-ever race. For Sunday’s race at the AVUS, he’d entered a privately owned Mercedes SSKL that’d been specifically streamlined by Germany’s leading aerodynamicists Reinhard von König-Fachsenfeld who was, naturally, a family acquaintance, as were, if you believed the gossip columns, the entire entry-list of Burke’s Peerage.

Sitting beside von Brauchitsch, and at an angle to the table, was a face I did not recognize. By the locus of his chair, he’d clearly either invited himself or been invited as an afterthought. He wore a cape over a black tuxedo and what appeared to be a top hat sat on the table before him. What kind of man, I wondered, placed his hat on a dining table? In that very instant the man’s eyes lifted and I knew then—I knew his stare would streak across the club and bore into my skull, a gaze that made my flesh crawl. I blinked, blinked the eyes away as Ditgens drew the curtains shut with a troubled sigh.

‘That,’ he said, looking at me skeptically, ‘is Hanussen.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘I don’t—’

‘The Great Hanussen.’

I frowned.

‘He has just completed a sell-out performance at The Scala Theatre.’

‘Ah,’ I said, weirdly relieved. ‘An opera singer.’

‘Not La Scala,’ Ditgens allowed himself the briefest of smiles with a mouth that had lost a good-few teeth. ‘The Scala. A theatre here in Berlin. The Great Hanussen, sir, is a world famous clairvoyant.’

‘Clairvoyant. ...’

‘Yes,’ Ditgens watched the passing of two men through the antechamber. He ignored them when they sought his approval, leaning in closer to me like a boxer ready to inflict a few chosen body hammer-blows. ‘Look, this Hanussen chap—I’m as skeptical as anyone, you understand Signor Finestrini—I really am. I’m a materialist man sir, I fought in the War, I don’t have any delusions to, to,’ his hand flapped about limp-wristed, ‘but that man gives me the creeps. He told me that tonight an Italian would come to the club wearing a knee-length gray loden coat.’

It took me no time find the comfort of the rational. ‘Varzi is expecting me, Herr Ditgens, and he has often commented on my coat—I’ve had it for years, you see. No doubt a practical joke—’

Ditgens was shaking his head, and I politely interrupted myself to its urgency. ‘No sir. No. Hanussen told me that he was here, tonight, in order to warn one of the men at that table.’

‘Warn?’

‘One of those men at that table is in grave danger, that’s what he said. Grave danger.’

I took a breath. ‘I don’t think I follow. If this is indeed the case, why does he not warn the man himself?’

‘I myself asked the same question. It is apparently not within his remit to do so.’

‘His ...’

‘Remit,’ repeated Ditgens, glancing up to assure himself that I shared his sense of disgust. ‘His remit.’

‘I see.’

Ditgens waited expectantly.

‘So what does this have to do with me?’

Ditgens seemed pleased that I’d finally asked. ‘I have no idea, other than that Herr Hanussen assured me it was urgent that I give you a message before you joined the table.’

‘A message?’

Ditgens had it in one meaty hand, a napkin stained with words written in a fierce spidery scrawl in Italian.

Signor Finestrini, it is incumbent upon you to save a man’s life tonight. I will do all I can to make the identity of this man known to you: What you then do is entirely up to you and your conscience. — The Great Hanussen

Ditgens waited for my face to rise.

‘Ah,’ I said.

‘Quite,’ he replied. Apparently relieved then, Ditgens parted the curtains and invited me into the club. Hanussen’s eyes were like a spotlight tracking my reluctant march through the dimness behind a wet, luminous intensity. I stepped toward the table with a dull apprehension. I remained dully convinced, though—despite the chill that ran up my spine—that this was some form of elaborate joke dreamt up by Varzi. Ditgens grabbed a pink-cushioned, violently decorated chair from a neighboring table and positioned it beside von Brauchitsch so that the Prussian now had Hanussen and I pressed up against him from either side.

‘Ditgens, just the man,’ said von Brauchitsch. ‘Champagne, my friend, champagne all ‘round, and be quick about it.’

‘And a Johnnie Walker, black, for Finestrini,’ added Varzi.

Ditgens walked away, and I felt his abandonment rather too keenly. Varzi jutted his chin out at Hanussen. ‘This is—’

‘Hanussen, the world famous clairvoyant,’ I interrupted. I wanted to look at the man, could sense his eyes on me, but somehow my muscles would not obey the apparent secularism of my mind.

‘Another clairvoyant!’ declared Baby Hoffman laughing. ‘My-my—’

‘Indeed,’ von Brauchitsch swilled some champagne in his mouth, blue-stained eyes tainted with open disgust, the sort of expression only millennia of wealth and affectation could manufacture, ‘but this one is but a fraud.’

I looked at him, the baron in his dirty jacket and slicked-back hair; at that face that smiled a sneer, at those eyes that welcomed my contempt, prompting me, mocking me. So much, I thought, for my interview, and fuck him anyway, him, his progeny, and his ancestors.

‘Hanussen was just about to read Charly’s mind,’ said Varzi, ‘weren’t you, Great Hanussen? I hope you’re prepared for the worst, Charly.’

‘There are no secrets at this table, surely,’ said Charly.

Hanussen, still as a lizard, gazed at her until she couldn’t do anything but meet his eyes. It was then that he glanced at Baby with an intensity that had Charly bow her face to her drink with what appeared to be a genuine disquiet. ‘Only the ones I choose not to divulge,’ he said with a voice that enraptured me. I looked across at him and discovered a set of pale fish-like eyes fixed on me. ‘It is, after all, non-incumbent upon man to alter destiny. Do you not believe this is so, Signor Finestrini?’

‘Destiny is a nonsense,’ said Chiron. ‘A man creates his destiny through hard work, dedication, endeavor—’

‘Not to mention talent,’ added Caracciola.

‘Do you know, Great Hanussen,’ continued Varzi, ‘who will win tomorrow’s race?’

Hanussen seemed to consider the question. ‘Were I to put my mind to it? Yes. Of course. But tell me sir, how would you feel to discover your destiny a thing already ordained? Tomorrow a thing already determined?’

‘Destiny is what we make of it,’ Prince Lobkowicz said. ‘Not even God would be so presumptuous as to preordain the finishing order of a motor-race.’

Hanussen bowed his head. Only a German, I thought, could reflect superiority in such a motion. ‘Indeed. God, I should imagine, has matters far more momentous to ponder than a motor-race; as a man of God yourself—for your family, I am told, is blessed with a special relationship with the Holy Father, is that right?—I rest certain that you don’t share the delusion that a motor-race matters. Despite my public persona, I can assure you—all of you—that I’m here as a friend, an ally. Signor Finestrini, you are the world’s pre-eminent motor-racing journalist, surely you are in the best position to speak to us about destiny. Destiny and its brother, superstition.’

‘The world’s pre-eminent motor-racing journalist?’ laughed Chiron. ‘Clairvoyant you may be, sir, but clearly you know little about journalism.’

I found and lit a cigarette. I noted my hand was still when I placed the flame on the edge, the tobacco crackling into my lungs. I glanced up at Hanussen. He stared back with a polite aggression. ‘One of the—that is, one of my earliest articles for the Gazzetta was a feature I did about a man named Count Zborowski, an American who had the good fortune to marry into the Astor family. He settled in England and there became one of the pioneers of motor-racing—he was one of Mercedes’ very first customers actually, Rudi. Anyway, I think it was in ’03, on the eve of a minor hillclimb event at La Turbie that he was given a gift of a set of gold cufflinks which he chose to wear on the day of the climb. On the way up, one cufflink got entangled with his hand-throttle, forcing the engine wide open and powering the poor man straight to his death.’

‘A bit tenuous, this link you’re making,’ said Varzi, grinning.

‘A number of years later,’ I continued, ‘some of you will probably recall his son, also racing as Count Zborowski—’

‘I remember him,’ interrupted Chiron. ‘Drove a Bugatti at the Indy 500, right?’

‘That’s the man, yes. In ’24, he was offered a factory drive for Mercedes just like his father. At Monza, on the anniversary of his father’s death, and as a mark of respect, the young Zborowski decided he would wear the very same cufflinks—’

‘Oh come now Finestrini,’ Caracciola smiled at me. ‘Surely you’re not about to suggest the theory of the killer cufflinks.’

I smiled back with a sincerity my mind seemed ill-disposed to afford my quaking heart.

‘So what did happen?’ asked Charly.

‘He crashed,’ I replied. ‘Hit a tree and was killed on the spot; same day, same hour as his father.’

Varzi clapped his hands, precisely twice. ‘Precious, Finestrini, precious. So the cufflinks were cursed?’

‘Pure maths,’ said Caracciola. ‘Nothing more than a numbers game—coincidence—or do you see the work of sinister forces at play, Herr Hanussen?’

‘You gentlemen live a perilous life sir, and far be it for me to question how you rationalize your risks.’ Hanussen held his hand out at me. ‘May I borrow your pen sir?’

‘I’m afraid I don’t have one.’

‘He’s an imminent journalist,’ Chiron said, rolling a gold monogrammed fountain pen at Hanussen. ‘Why should he carry a pen when he doesn’t even attend half the races he writes about?’

Hanussen took the pen and balanced it above a napkin. ‘Tomorrow,’ he said, ‘one of you here, at this table, will win the race at the AVUS.’

We all watched as Hanussen wrote on the napkin.

‘A lot of letters,’ said von Brauchitsch.

‘A lot of shit,’ said Hans Stuck.

‘Well yes,’ admitted the baron, ‘Stuck and shit may be mistaken for each other I suppose.’

Hanussen searched in his pocket, found and withdrew an envelope into which he placed the napkin. With a ceremonious certainty, he sealed it with his tongue and dropped the envelope on the white linen tablecloth. ‘I have placed,’ he said, turning to von Brauchitsch, ‘two names in this envelope.’

‘Two?’ asked Baby mockingly. ‘Herr Hanussen, there’s only one winner in a motor-race.’

Hanussen rose from the table. He lifted the envelope and held it out suddenly. At me. I accepted it, aware of my own hesitation, unable to explain my own unease. He lifted his top hat which he now held at his chest, a hymn, I thought, to his own madness. ‘Only one victor sits at this table, madam, this much is true. But it is equally true that here sits a man who has enjoyed his last supper, too.’ Hanussen the showman allowed the words to ride across the table on their own tide of rectitude. ‘In that envelope I have written those names. Now,’ he assembled his things, did Hanussen, his eyes already projecting themselves across the expanse of the Roxy and ignoring us lest he give something away, ‘I must bid you all goodnight ... and farewell.’

We watched Hanussen stride away from our table, his abnormal silhouette quivering amidst the tables, watched him throw the curtains apart, those black velvet curtains like the devil’s wings that flittered him away into the cold of a Berlin night.

‘What a horrid little man,’ whispered Charly.

I placed the envelope on the table. A hush had settled over us, swallowing the noise even from the floorshow. Ditgens chose that moment to materialize, pouring pink champagne into our thirsty flutes. He pointed at the stage where a razor-thin woman—with a cigarette between juicy, crimson lips—sat on a revolving stool with legs splayed. ‘She’ll be famous one day,’ he declared.

As those about me focused their attention on the woman whose mouth wept a sound as deep as the clouds of smoke on ceiling above us, I slid the envelope into my breast pocket. When I looked up, all eyes were watching the woman but for one set: Varzi’s, who stared first at my face, then down at my heart. A tiny smile played on his lips when he shared a whispered aside with Chiron. Chiron lifted his face and snatched a glimpse at my face before looking away just as quickly. It was not long after that I found an excuse to leave the Roxy and return to my room at the Adlon.

I hung my dinner jacket in the closet and, still clothed against the chill, sat behind the desk to review my notes and sort my lapchart out for the race to come. But that envelope—that envelope soon became a noose for my words. Was I meant to open it? And if I did, what then? What was it that I was meant to do should I unseal Hanussen’s spit and read those two names? Warn the man who Hanussen maintained would die tomorrow? And how was I to do that, I thought, becoming further agitated with every passing deliberation. Would it not be the case that, should I interfere with a driver’s mind—Excuse me, sir, but you do know you’re about to die today?—would I not be creating the very doubt that could kill him? A driver lived on intuition, survived by sheer faith in his own ability: Were I to strip that away, I could well be the cause of an accident—of a death.

And should I ignore it? Ignore Hanussen—would I not then be equally culpable?

It was past midnight—well past—when I finally resolved the situation. With the closet buried in the graveyard blackness of my room, I decided this was nothing more than a cruel joke perpetrated by that bastard Varzi. And even if it wasn’t—was I really to believe in the clairvoyance of a man I’d never set eyes upon until that very evening? The Great fucking Hanussen, who was he anyway? Aside from a worm who’d succeeded in burrowing his way into my soul, secreting fear.

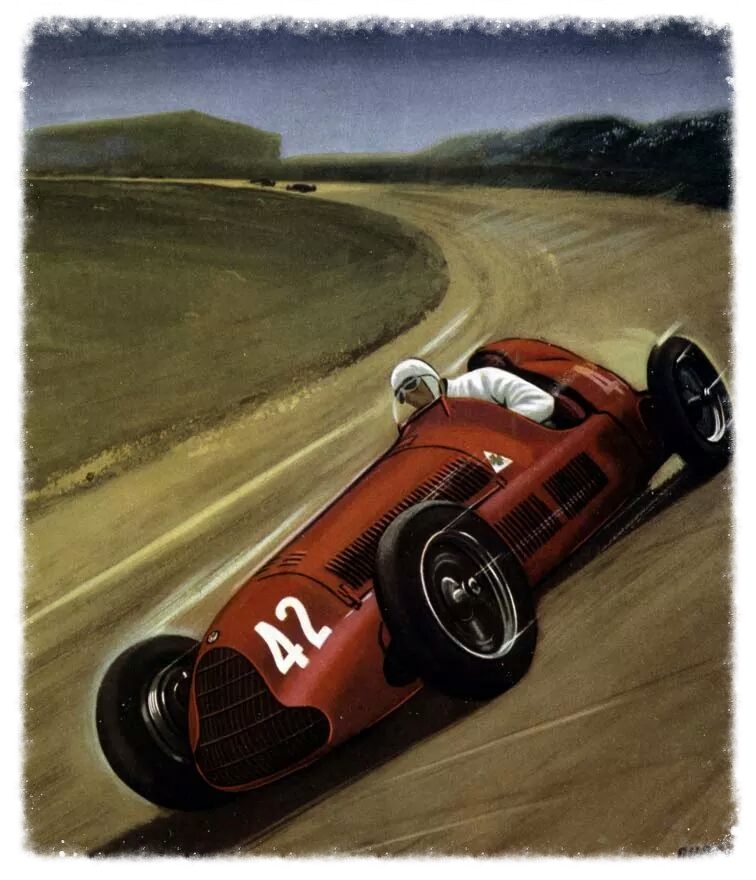

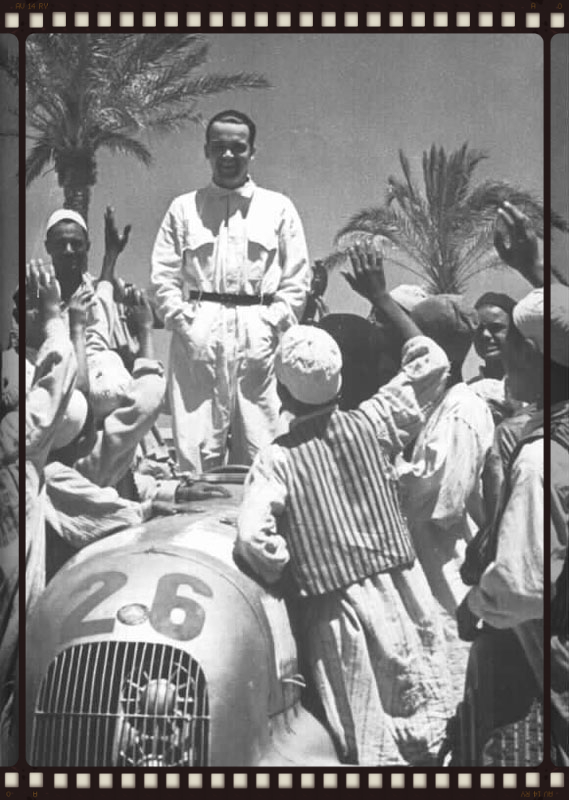

Caracciola in typically imperious form at Tripoli in 37: Caratch was seriously superstitious and would take with him all sorts of lucky trinkets to race weekends

A troubled night ended in a crisp and welcome dawn. At seven that morning I resolved to pack my notebook and set off for the circuit after a stolen cup of coffee and a butter croissant. I’d almost reached the revolving doors and the Berlin morning too, when a voice whispered my name. Charly Caracciola stood with an overcoat over her shoulders beneath the staircase, wide blue eyes beckoning. Her body seemed charged by an obvious anxiety chewing at her kind complexion. ‘Signor Finestrini,’ she whispered, her arms hugging herself tightly in the velvet hush of the Adlon, ‘you understand, you are Italian, you understand—it was here, at the AVUS, where Rudi, where our destiny—you understand—’

‘I’m afraid I don’t,’ I replied.

‘If something, something were to happen—’ I listened as Charly confessed to not having slept a wink that night. ‘That horrid little man,’ she said. ‘He infested my dreams.’

I faked a laugh; it sounded shrill in the vast lobby, obscene. ‘That man is a fraud, Charly.’

‘Still,’ she insisted, staring down at her pink ballet shoes. ‘Still.’ Her eyes came up to meet mine and there was isolation there, an insistence. ‘I think we—that is, Rudi—would feel better, if we,’ she grabbed my arm then, her cold fingers pressed tight on my wrist, ‘tell me what was written in that envelope.’

I don’t know why the lie came so easily to my lips; a lie, I suppose, is always smoother in the company of beauty. ‘The envelope? Why, you know, I think I left it at the club. Really,’ I smiled, holding her hands in mine and addressing them, ‘Charly, you have nothing to worry about. This is the AVUS, a man like Rudi will never come to any harm here, not on this track. Come, you know this ...’

I escorted her back to the gleaming bank of elevators and waited for the metal lips to shut away my guilt before heading out to the track. I spent the morning up in the tower over the back-straight with Paul Levant who was to do the live broadcast for German radio and with whom I enjoyed a friendship that dated back to our first meeting at Monza in ’29. It was from Levant that I first heard the rumor—confirmed later that morning through a press release from Bugatti-chief Constantini—that Varzi and Chiron had pulled out of the race due to a clerical error that had the pair on the entry-list for two simultaneous races, one here in Berlin, the other in Casablanca. In order to avoid disqualification and sanctions by the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus, Constantini had taken the decision to replace Chiron and Varzi with Divo and Bouriat respectively. An odd thing, and one that apparently had not sat well with the chief steward who had, he claimed, no intention of disqualifying either of Bugatti’s star drivers. Had the events at the Roxy somehow unnerved them?

The colossal clock above the grandstand tipped over to 4PM when the drivers, who I’d taken great pains at avoiding all day, came under starter’s orders beneath a sparkling blue sky. Over a half-million spectators had come out to enjoy the first important German motor-sport event of the year, and they stood to the tune of sixteen engines firing up in the cool afternoon, Divo, Caracciola, and von Morgen on the front row, Lobkowicz bringing up the rear.

Levant would be using my lapchart for his live bulletin, and I was too busy updating it on his behalf to spot what had him suddenly shouting into his microphone. His sudden excitement had me look up, standing to better see the track spread out into the horizon below us, my hand instinctively grabbing a set of binoculars. I could see the strand of cars headed for the South Loop through the Grunewald. Just south of the Forsthaus into the languid kink where the cars entered the tricky braking zone for the hairpin, Lobkowicz, Lewy, and Willy Williams—all in identical blue Bugattis—were side-by-side, wheels practically entwined. As they flashed beneath the Havelchaussee underpass, Lobkowicz scampered right and away from Williams’s Bugatti. To his right, inches away, Lewy reacted instinctively, darting to his right. I could see a flash of flames as Lewy scraped the concrete wall of the underpass with a rear wheel. Lewy, losing control, came back across the track heading helplessly for Lobkowicz who threw his car to the left, slamming on his brakes as Williams tore past the both of them. At over 200KM/H, Lobkowicz tried to catch the slide that his reaction had provoked. Caught it too—but he’d borrowed too much—borrowed too much and the T54 shivered into a pendulum-like motion, the rear trying to swap corners with the nose. And then, just like that, it was gone, the Bugatti pirouetting away across the track. The car recoiled over the eight metre grass median before scuttling into the railway lines that wedged the car up into the air. The Bugatti exploded into a silent symphony of shredded metal beyond my lenses, body parts leaping into the crystal-clear spring evening, cartwheeling away into the scenery. In that star-burst of mechanical parts I traced Prince Lobkowicz tossed into the afternoon like a child’s unwanted ragdoll.

I was vaguely aware of the silence. Levant’s silence, the silence of the crowd. In the distance engines scraped, rasped, supremely indifferent to the corpse lying there in the dirt just beyond the South Bend. From the green belt of the Grunewald the cars burst out like an orgasm, Divo leading with a shower of sparks in his wake. Car after car sped past the body of Prince Lobkowicz, his white one-piece racing suit so utterly still, slumped on the outside of the turn. Levant, composed, returned his mouth to the microphone. I rested the binoculars onto the desk as Dreyfus chattered by leading Divo by a breath. I walked away then, down the one-tone concrete stairs into a tranquil afternoon through which the sounds of the engines shrieked. Levant’s words followed me to my car via the PA. ‘Von Brauchitsch has taken the lead, and the half million spectators here today at the AVUS hail their new hero in his silver arrow. Here he comes now, and the crowd responds—listen to that!—they’re chanting a name we’re all sure to hear many times in the years to come. Von Brauchitsch, von Brauchitsch!’

Silver arrow, I thought, motoring away from the track. Silver arrow ...

In my room at the Adlon, I set about drafting my copy while nibbling on an oily bratwurst brought up by room service. Von Brauchitsch’s victory had been as popular as it had been unexpected, and dislike the little jerk as I did, I couldn’t but be impressed at the way he had secured his reputation that afternoon. His style behind the wheel—unlike most drivers I’d come to know over the years—was a carbon-copy of his personality; irreverent, aggressive, and down-cold nasty. His face, under that red silk helmet of his, had turned crimson with fatigue (and redder still with rage when in a battle for position). He was fierce, uncompromising, and as crude as a serial drunk. He was also quick and brave, and I toyed with the idea of writing a story entitled ‘The Adventures of Baron von Brauchitsch’. Instead, I settled for a piece that questioned Italy’s dominance of the sport should the Germans ever choose to return to the fray little realizing the real story hid in my jacket pocket. Today, I wrote, Mercedes had shown how superior their aerodynamic understanding was, and how developed, too, the German alloy industry was compared to Italy. These were, I added, halcyon days for Italian motor-racing, and certainly Germany could not produce a racing driver of the caliber of a Varzi or a Nuvolari in a generation. But was that reason enough for our motor-car manufacturers to choose this moment to rest on their laurels? If, I concluded, the answer was yes, and should the fully-funded Silver Arrows return to competition, we would come to regret our impertinence.

The phone was ringing when I’d stepped from the shower with the story safely filed with Milan exchange, the night a solid dark mass beyond my window. ‘I’m at the bar, downstairs,’ I heard Varzi say. ‘Come down. We need to speak with you.’

‘We?’ I asked, shuffling my hair with a comb and noticing a gray strand just south of my temple in my hand mirror.

‘Now,’ said Varzi.

They were sitting in a booth near the windows through which a street-light painted a dull yellow scepter over the parquet floor. Charly, Caracciola, Chiron, Baby Hoffman, and Varzi, all watching me come.

‘Sit, sit,’ Varzi patted a chair set-up for me square with the booth. He waited for me to obey before leaning in closer. ‘Come on then, out with it.’

‘Sorry?’ I asked, glancing about the bar.

Varzi gave me the benefit of one of those silent stares of his. Lost in its cruelty, I didn’t notice, for a good while, that his hand lay, palm up, between my elbows. ‘Oh,’ I whispered, aware suddenly of eyes watching my every gesture. ‘Oh, right.’ I found the envelope in my jacket and handed it over, chancing a quick glance at Charly who made a concerted effort to ignore me, looking away, down at Varzi’s hand that tore at the envelope’s edge. He read the words on the napkin and a sly smile came across his face.

‘What does it say?’ asked Charly.

‘Probably an invoice,’ said Chiron.

Varzi splayed the napkin onto the table and sat back as we all craned our necks forward to read the two names written there in black.

Von Brauchitsch — Lobkowicz

‘My God,’ whispered Charly.

‘I’ll be damned,’ said Caracciola.

‘Why?’ asked Chiron

We turned to him.

‘Why didn’t Hanussen do anything?’

***

Caracciola and 'Baby' Hoffman: she spoke five languages, and invented the viewing tower at Indy; when she was barred from the pits, being a woman, she had a tower built in the in-field from which she could time the race. She had left her husband, the heir to a major company, for the debonair Louis Chiron, before falling in love with Caracciola after Charly's death. Charly, herself clairvoyant. had given Baby a photo of Baby and Caratch, and had written that Baby's future would be with Caratch when she died. Charly died some weeks after, and Baby and Caracciola would remain married until his death, twenty years later.

‘Why didn’t you?’ I ask.

Finestrini sits back in his seat. Out there where he stares, the Bora is soaring, menacing and angry. A man holds onto the metal bars of the boardwalk, the wind contorting his body as if he were a mime-artist. ‘I was told later that Hanussen had tried to contact the authorities to ban Lobkowicz from the race; his efforts were ignored.’

‘At which point—’

‘At which point he apparently turned to me.’

‘But you never opened the envelope. Did you?’

‘You know,’ Finestrini replies, ignoring my question, ‘a year later Hanussen was found dead in a shallow grave on the side of the Berlin—Dresden motorway. Suicide was the official verdict.’

‘And the unofficial one?’

Finestrini turns from the wind to jut his chin at my notebook. ‘Since you’ve failed to make one note all morning, I’ll tell you something interesting. After the war I had a chance encounter with Herr Ditgens on the night train to Geneva, and naturally our conversation turned to that strange night at the Roxy. Ditgens told me that Hanussen, over the winter of ’32, had become a close companion of Hitler. Ditgens was convinced Hanussen had taught Hitler the art of mind control, mass hypnosis through the use of speech and hand movements—’

‘Many Germans after the war,’ I interrupt, ‘looked at irrational—’

Finestrini indulges me with a look that shuts me up. ‘This is not a sociology book you’re writing, is it?’ He let’s that sink in for an instant. ‘Do you know,’ he continues, ‘that Hanussen actually predicted the Reichstag fire?’

‘Did he really?’

‘Indeed. Two weeks before, actually, at The Scala. But the issue of Hanussen’s clairvoyance came into question when it became known that he and the man who was blamed for starting the fire—van der Lubbe—had been seen in each other’s company a week before the fire. Ditgens told me he believed Hanussen had somehow hypnotized the young lad; and then, being a Jew and a loose end, Hanussen was disposed of by the SA. Which makes sense since his suicide—when the files were re-opened after the war—offered some, how do you Americans say? tantalizing clues?’

‘Such as?’

‘He was found in a grave with a bullet in his head and no gun at the scene. So unless the Great Hanussen managed to dig a grave after he shot himself in the head without a gun ...’

I open my folder and find an article dated December 1940. ‘Tell me,’ I slide the cut-out across the table toward the eggshells, ‘did you feel any guilt?’

Finestrini’s eyes follow my hand. ‘Should I have opened that envelope, is that what you’re implying?’

‘He asked you to, didn’t he? Hanussen?’

‘Did he?’

‘He wouldn’t have involved you otherwise.’

‘I rationalized my guilt fifty years ago,’ Finestrini says, accepting the cut-out with the Bora rushing by like speed. With his spectacles balanced on the bridge of his nose, he turns the words to the sprinting light of day.

Caratch, another win, 1937

The Mechanics of Superstition

The superstition of science would, at first reading, appear a contradiction; and yet, in my experience, there are few racing drivers who do not live — which is to say race — divorced from the undue influence of superstition hanging over their heads like the proverbial Sword of Damocles. In the mechanical — let us say scientific — world of grand prix racing, where men earn a living risking death, it is not, as one would expect, science, or indeed the mechanical craft of their art to which they entrust their destinies. No, it is precisely the opposite: It is a pagan-like devotion to superstition that these men turn to.

Even the trifling matter of color is of crucial concern to your average driver. Green, in the earliest days of motor-racing, was the unluckiest of pigment, and one would be hard-pressed to find any grand prix driver brave enough to throw his destiny into the sheet-metal confines of fate, sheathed in green. But all of this changed when Charles Jarratt’s Panhard won the 1901 Paris−Berlin motor-race, a feat of such momentous proportions that the color became synonymous with good fortune amongst the British, that most materialist of people. For others on the Continent, however, green remains the shade of ill-fortune, the color of malice.

It is also a scientific truth that, should one attach one’s destiny to a particular superstition — a number, say, or a charm — one is best served by always remaining faithful to ritual, for fate is never kind to the fickle of heart, to the devotionally insincere. This is born out by empirical certitude. Take, for instance, Herman Lang, whose wife always nailed a horseshoe in her husband’s pits: At Masaryk in ’37, she misplaced the charm and Lang had the biggest shunt of his career. But where Lang and Caracciola (and his arcane, almost cabalistic process of preparation) survived, Dick Seaman — the only true Titan produced by the British before this war that is consigning our racing tradition to a pyre — was to pay the ultimate price. Seaman was well-known to harbor an aversion for the number 13: At Spa in 1939 — 3 times 13 — there were 13 cars entered for the race. Seaman’s Mercedes was numbered 26, and he was born in 1913. His name was placed 13th on that day’s race-entry list. And his accident occurred with 13 laps remaining in the race, at La Source, which was at the 13 kilometre mark on the track. He succumbed to his wounds at a local hospital in room 39.

At the age of 26.

Such examples are both ripe and lore in motor-racing, and while we wait for science to provide us with an explanation as to why our pagan beliefs are invalid, superstition will continue — in the mechanical world of motor-racing — to trump the sanguinity of science.